Here’s something that’ll mess with your head: you’re probably wrong about how good you are at most things. Not just a little wrong—wildly, embarrassingly wrong. And the kicker? The worse you are at something, the more convinced you’ll be that you’re actually pretty great at it.

Welcome to the Dunning-Kruger effect, one of psychology’s most fascinating findings that explains why your uncle thinks he knows more about vaccines than doctors, and why that guy who just got his driver’s license is already convinced he’s the next Formula 1 champion.

The Study That Changed Everything

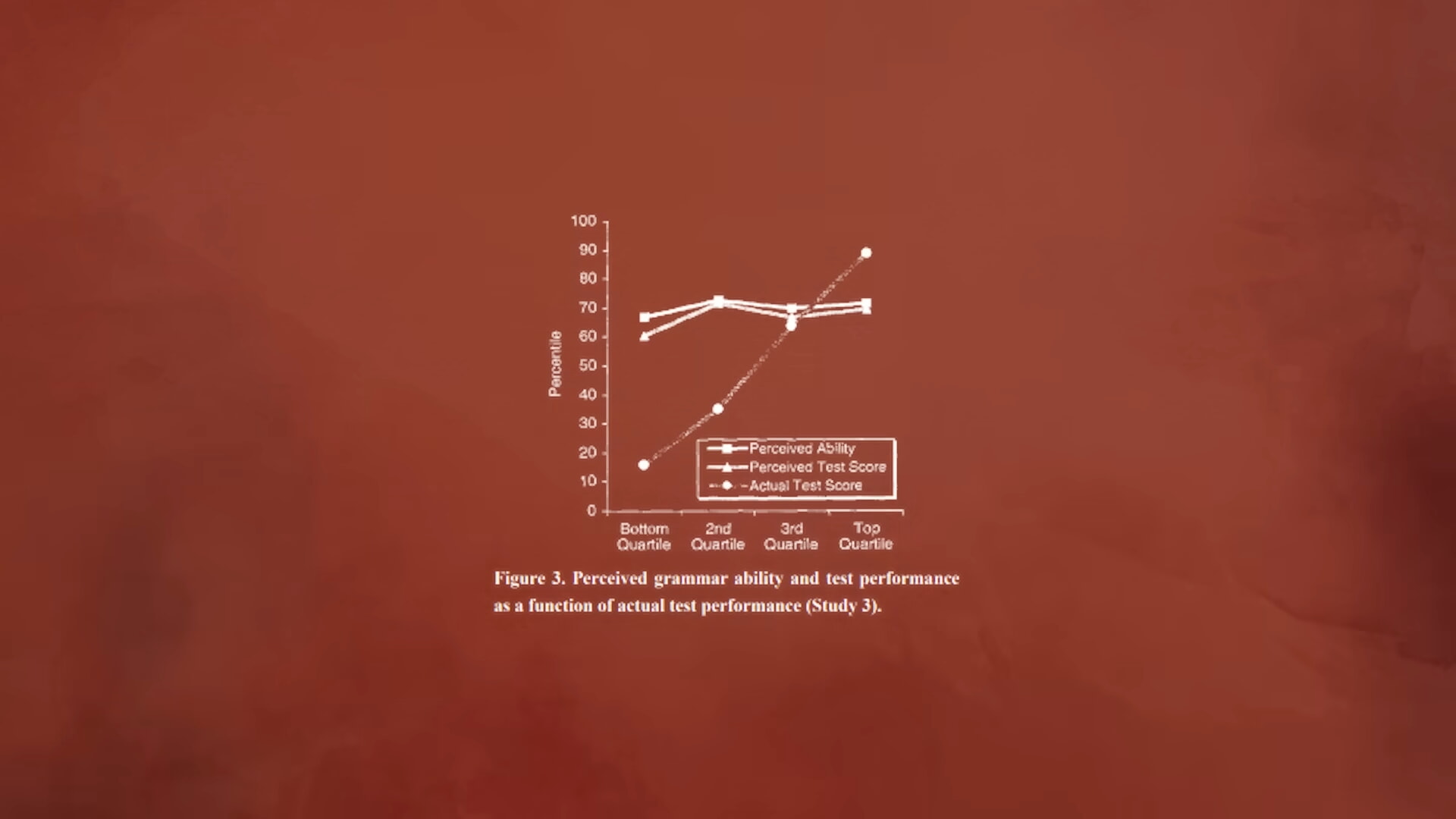

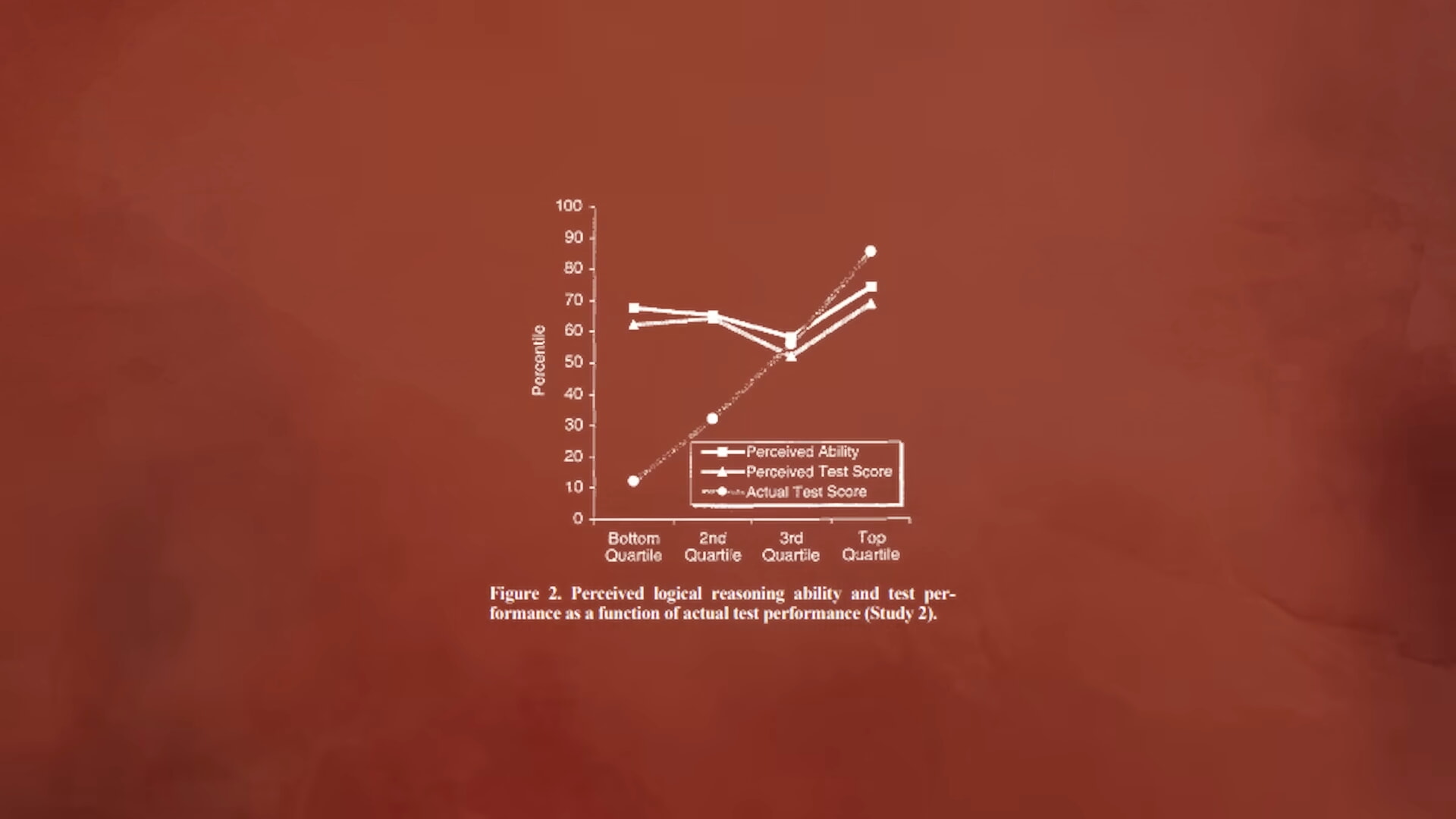

Back in 1999, psychologists David Dunning and Justin Kruger ran a study that would blow everyone’s minds. They gave people tests on humor, logical reasoning, and grammar—pretty standard stuff. But here’s where it got interesting: after the tests, they asked everyone to guess how well they did compared to other people.

What they found was bonkers. The people who bombed the tests thought they absolutely crushed them. Meanwhile, the folks who actually did well were sitting there thinking, “Eh, I probably did okay, I guess.”

It wasn’t just a fluke. This pattern showed up again and again. The less someone knew, the more confident they were. The more someone actually knew, the more they doubted themselves.

Why Our Brains Play These Tricks

The explanation is both simple and mind-bending. If you don’t know much about something, you literally don’t know enough to realize how much you don’t know. It’s like being lost but not having a map to show you just how lost you really are.

As Dunning put it: “If you’re incompetent, you can’t know you’re incompetent… the skills you need to produce a right answer are exactly the skills you need to recognize what a right answer is.”

On the flip side, people who really know their stuff understand just how complicated and vast their field is. They’ve seen enough to know there’s always more to learn, more ways to mess up, more nuances they haven’t mastered yet. So they’re naturally more cautious about claiming they’re experts.

This Stuff Is Everywhere

Once you know about the Dunning-Kruger effect, you’ll start seeing it everywhere. Remember that stat about 93% of American drivers thinking they’re better than average? Yeah, that’s mathematically impossible, but there it is.

In the workplace, it’s even more ridiculous. Studies show that over 40% of employees think they’re in the top 5% of performers at their company. Again, the math doesn’t work, but human psychology sure does.

The Metacognition Connection

Here’s where things get really interesting. There’s this thing called metacognition—basically, thinking about thinking. It’s your brain’s ability to step back and analyze your own thought processes, catch your mistakes, and figure out what you need to work on.

When you’re incompetent at something, you’re also bad at metacognition in that area. You can’t spot your own errors because you don’t have the skills to recognize what good performance even looks like. It’s like being colorblind and trying to critique a painting—you’re missing the tools you need to make accurate judgments.

Why This Should Scare You

Individual ignorance is one thing, but when you scale this up to society, it gets genuinely frightening. The people who know the least about complex topics are often the most confident and vocal about them. Meanwhile, the actual experts are over there being all careful and nuanced and boring.

As Dunning noted: “What’s curious is that, in many cases, incompetence does not leave people disoriented, perplexed, or cautious. Instead, the incompetent are often blessed with an inappropriate confidence, buoyed by something that feels to them like knowledge.”

So, who’s more convincing to the average person: the loud, confident amateur who speaks in absolutes, or the careful expert who acknowledges complexity and uncertainty? Unfortunately, we all know the answer.

The Voice Problem

We’re living in an age where everyone has an opinion about everything. Maybe it’s social media, maybe it’s always been this way, but it feels like the loudest voices are often the least informed ones.

The real experts? They’re usually the quiet ones, still figuring out how to explain complex ideas to people who don’t have their background. They’re not great at soundbites because they understand that real answers are usually complicated and messy.

The Trap You Can’t Escape

Here’s the really messed-up part: knowing about the Dunning-Kruger effect doesn’t make you immune to it. In fact, thinking you’re now above it is itself an example of the effect in action.

“The first rule of the Dunning-Kruger club is that you don’t know you’re a member of the Dunning-Kruger club,” Dunning said. You know just enough about the phenomenon to think you can avoid it, while not knowing enough to realize you probably can’t.

How to Fight Back (Sort Of)

The truth is, most of us are only truly knowledgeable and experienced in a handful of areas at best. And that’s okay! We don’t need to be experts in everything. We shouldn’t pretend to be.

The key might be getting comfortable with being quiet more often. Being okay with not having an opinion on every topic. Letting your voice, your presence, your hot takes sit this one out sometimes.

After a certain point, the more opinions you hold, the worse quality they probably are. We’re all going to fail at knowing where our expertise ends and our ignorance begins, but at least we can try to be aware of it.

The Never-Ending Cycle

The Dunning-Kruger effect isn’t something you overcome once and then you’re done. It’s a sliding scale that follows you through life. Every time you start something new, you’ll be incompetent again. Every time you’re incompetent, you’ll be partially blind to just how incompetent you are.

But here’s the good news: as you learn and grow, you’ll keep realizing how much you didn’t know before. Life becomes this continuous cycle of thinking “Wow, I was really wrong about that” and “This is way more complicated than I thought.”

And honestly? That’s not such a bad way to live. The moment you stop being surprised by how much you don’t know is probably the moment you stop growing.

So the next time you catch yourself feeling supremely confident about something, maybe take a step back. Ask yourself: do I actually know what I’m talking about, or do I just not know enough to know that I don’t know what I’m talking about?

Your brain might be playing tricks on you. And that’s perfectly, frustratingly human.